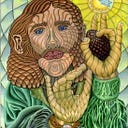

1. Sages have Life Force (Jing) in their Core

Nei-yeh: Ancient Chinese Self-Cultivation Manual

The Nei-yeh is an ancient Chinese self-cultivation manual. Its ultimate focus is upon how to maximize human vitality. To accomplish this aim, it provides techniques that presumably optimize the interactions of a holistic network of integrated, yet separable, energies and processes.

This article provides a line-by-line analysis of the first verse. For more check out Nei-yeh: Cultivating the 3 Jewels (Energies).

1 The vital essence (jing) of all things:

2 It is this that brings them to life (shêng).

3 It generates the 5 grains below

4 And becomes the constellated stars above.

5 When flowing amid the heavens and the earth

6 We call it numinous (shên) and ghostly.

7 When stored within the chests of humans,

8 We call them Sages (sheng).1

Commentary

Following is a line-by-line analysis of the first verse of this self-cultivation manual. In the Nei-yeh, the first line frequently clearly identifies the verse’s focus. In this verse, the topic is jing, translated as ‘vital essence’. Related to sexual energy in the Freudian sense, I prefer to think of jing as Life Force.

Lines 1–4:

1 The vital essence (jing) of all things:

2 It is this that brings them to life (shêng).

3 It generates the 5 grains below

4 And becomes the constellated stars above.

The first 4 lines of Verse 1 report that jing is a generative force that brings things to life. It is the source of life/vitality (shêng). As a source of living vitality, jing is not merely mechanical energy. Chinese medicine continues to associate jing with an individual’s life force all the way into the 21st century. Indeed jing, along with ch’i and shen, are considered to be the 3 jewels of Chinese medicine. The Nei-yeh invests a considerable amount of its terse text on the relationship between these ‘3 jewels’, vitality and the Tao.

Lines 5 & 6:

5 When flowing amid the heavens and the earth

6 We call it numinous (shên) and ghostly.

When jing flows between Heaven and Earth, it is called ‘numinous and ghostly’, i.e. heavenly and earthly spirits. For the Chinese, the heavenly spirits were very likely associated with nature, such as a particular hill or river. Earthly spirits probably took the form of human ghosts, such as those that have died prematurely. Jing seems to be the animating force of the spirit world as well the life force of biological creatures (lines 1–4). As the animating force of individual humans, jing seems similar to the life-giving energy that many associate with the concept of a soul.

Lines 7 & 8:

7 When stored within the chests of humans,

8 We call them Sages (sheng).3

Those that have jing ‘stored in their chests’ are considered Sages. Line 7 includes the highly significant ideogram for zhöng, i.e. center or core. The meaning of this particular ideogram locates jing, not merely in the general chest region, but more particularly in the core (zhöng) of the chests of Sages. The chest’s biological and metaphorical center is the heart (hsin). Sages have jing stored in their core or heart.

Due to its association with human vitality, jing seems to be a cosmic energy source that we want inside of us. Verse 1 poses an unspoken question. How do we get jing’s generative energy into our core (zhöng) and become Sage-like?

Zhöng (the middle or core): Ideogram

Jing, Sage and zhöng (core) are important word-concepts in the Nei-yeh in particular and for the Chinese in general. Due to their significance both for this text and culturally, let us examine these word-concepts in more detail.

Let us begin with zhöng4. In this verse, Roth translates zhöng as ‘within’. I prefer ‘center’ or ‘core’. It is most commonly translated as ‘middle’.

In the Chinese/English Dictionary, zhöng is translated as:

1) center, middle;

2) in, among;

3) between two extremes;

4) medium;

5) China.

Zhöng’s overlay of meanings indicates that being in the ‘middle’ or ‘among’ or ‘within’ or even in the Middle Kingdom (China) also includes a context of dynamic tension ‘between two extremes’.

Zhöng’s ideogram is simple and yet instructive — a vertical line through the center of a box.

“It represents a square target, pierced in its center by an arrow.”5 By extension, some other translations of the word zhöng include, “To hit the center, to attain.”6

While the Nei-yeh tends to employ zhöng as a location, this symbol, in certain contexts, does not just represent the center, but instead has the connotation of achieving the center. ‘Attaining the center’ is a significant feature of Tai Chi practice as well as Chinese thought. This is not a passive state. Attaining the center in the context of the dynamic tension of life requires a constant redefinition and re-attainment of the center.

Zhöng combined with other key ideograms represents some very significant concepts in Chinese culture. For instance, the Chinese refer to their country, not by a formal name, but simply as the Middle Kingdom (zhöng guo), i.e. the core of the empire. Asian martial arts focus upon minimizing both movement and energy expenditure by maintaining central equilibrium around the center-line, i.e. the spine, and even the center point. Further when zhöng is combined with the ideogram for heart (hsin), it means ‘one’s center’.

To further indicate the importance of the word-concept zhöng to the Chinese, this ideogram is also used extensively in Chinese calligraphy to construct other more complicated ideograms.