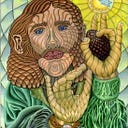

Rama & Sita, lovers & soul mates

The Virtue of Passionate Couple Love

- Concept of ‘soul mates’ unique to Hindu Mythology

- Pursuit of desires important to fulfillment of destiny

- Evil desires of the demons lead to their doom

- Romantic Love in the Secular Context

- Rama’s Insistence on Sita’s purity, a patriarchal flaw

The Ramayana and the Mahabharata, both written thousands of years ago, could be considered the ‘bibles’ of Hinduism. The influence of the Ramayana on Indian and Southeast Asian culture cannot be overestimated. Theatre, dance, philosophy and literature have revisited the story’s classic themes countless times over the centuries.

Rama, the hero of the story, epitomizes the good warrior king. He has another aspect which isn’t at all typical and which makes the appeal of the story even more universal. Let us take a look at the plot of the Ramayana to see what that aspect may be.

People adored Rama even as a child. Perhaps those around him sensed his divine nature. By the time Rama reaches adulthood, he is loved and respected by all. One of Rama’s first challenges as an adult is to protect a Sage as he performed a great yagna, a sacrificial ceremony. After this ceremony, the Sage suggests that Rama take an ‘interlude’ and go to a certain city which was having a festival. The Sage knows full well that this excursion would change Rama’s life.

As he arrives in the city, Rama, the young warrior prince, sees Sita, the princess of the city. From this one glance, Rama falls madly in love with Sita, just as she falls madly in love with him. Rama is the incarnation of Vishnu, and Sita is the incarnation of Vishnu’s heavenly consort, Lakshmi. They are unaware that they are a divine couple in heaven.

This powerful attraction, rooted in divine origin, is their destiny waiting to unfold. They are soul mates, who have found each other in this world. They may have forgotten their godly origins, but their passion for one another is immediate. No other man or woman has had this kind of an effect on either of them. It is because they are ‘soul mates’ destined to be a couple.

From just one glance, they are both sick with passion, unable to think of anything else but each other. Prior to this point, both had been balanced individuals. Yet now their minds are agitated and they can find no peace. Thinking of how beautiful Sita is, Rama makes the interesting comment:

“every item of those features seemingly poised to attack and quell me — me on whose bow depended the destruction of demons, now at the mercy of one who wields only a bow of sugarcane and uses flowers for arrows …,” (The Ramayana, p.26)

Rama is obviously overwhelmed by his passion for Sita. This same passion eventually inspires him to do battle with Ravana the evil Demon King. Ravana’s abduction of Sita led Rama to perform heroic deeds. Rama ultimately defeats Ravana, thus ridding the Earth of evil.

Concept of ‘soul mates’ unique to Hindu Mythology

Rama and Sita epitomize the concept of ‘soul mates’. This notion is a major feature of Hindu mythology* The transformative power of couple love is a key feature of Hinduism’s Ramayana. The mythology of the Ramayana permeates Southeast Asian culture. The central theme of the whole story is based upon the separation of Rama and Sita and their reunion. Rama is not motivated to engage Ravana the evil Demon King in order to protect his kingdom. Nor is he consciously driven by any divine directive. The dramatic action of the tale is solely driven by their love for each other.

In contrast, it is unusual for passionate couple love to be portrayed as a virtue in modern religions. Neither the teachings of Jesus, nor Buddha, nor Lao Tzu, nor Mohammed, nor the Old Testament Bible include the idea that the passionate love associated with a soul mate is a positive element in life. None of these teachings contains a prominent powerful couple. As we shall see, most religions consider this passion either a sign of weakness, a passing phase, or a temptation that must be overcome.

Let us begin a comparison of traditions by exploring some examples from the Old Testament. While there are hints of deep couple love in the Bible, they are certainly not highlighted and are frequently tainted. One of the more positive examples of couple love in the Bible concerns Jacob and Rachel. Jacob meets and immediately falls in love with Rachel. Her father, Laban, demands that Jacob must first labor for seven years and marry his older daughter, Leah. Then he must work seven more years before he can finally claim Rachel as his bride. The central theme of this story, far from idealizing the potent love of a soul mate, seems to focus on the culturally imposed ordeals associated with ancient marriage rites.

Indeed, the passion of couple love is rarely, if ever, held up as a virtue in the Old Testament. While there is passion in the Bible, most of the time it is problematic. For instance, Samson is destroyed by his passion for Delilah. An orthodox interpretation of the Bible’s initial example of couple love portrays Eve as the corrupter of Adam.

One prominent example that illustrates the temptations for ‘sinful’ behavior associated with passionate love is the story of David and Bathsheba. It could be argued that David was truly in love with Bathsheba. Unfortunately, she is someone else’s wife. This epitomizes an illicit love affair driven by passion. One consequence of this affair is that their first-born is cursed to die. Further, David sends Bathsheba’s husband to the front lines, where the probability of death on the battlefield was high. In a sense, David in this scene from the Bible plays the part of the Ramayana’s Ravana.

This is hardly the prototype of a healthy passionate relationship, such as Rama and Sita have. Generally speaking, it is evident that the Bible does not validate the positive sense of the passion and devotion that Rama and Sita have for each other. The couple love of soul mates is not a Biblical virtue.

Not only is passion for one’s soul mate not a virtue in the Old Testament, it is generally viewed in a negative light by other religious traditions as well. In general, the traditions of Christianity, Buddhism, Yoga, and even Taoism tend to view the passion of couple love as a distraction from the spiritual path. Neither Buddha, nor Jesus, nor Lao Tzu even had a sexual partner. Monks, whether Yogic, Buddhist or Christian, take a vow of celibacy in order to channel their bodily passion into spiritual passion.

This way of thinking degrades the importance of the Body, while elevating the importance of the Mind. Bodily desires, rather than being considered divine, are transformed into an evil that must be resisted. This resistance is viewed as a significant step on the path to enlightenment. From this perspective, the carnal desires inspired by women corrupt the true spiritual craving of man.

Just as the passion of couple love is thought to get in the way of the spiritual path, it also interferes with a primary Chinese cultural virtue — filial piety. Filial piety is closely associated with a particularly deep respect for father, family, and government. The intense passion associated with soul mates generally represents unwanted competition for this expected loyalty to the paternalistic family or state.

When the father selects the husband for his daughter, he does so in order to create or strengthen a family alliance. He rarely, if ever, considers the romantic attraction of a couple as a factor in his decision. The Chinese downplay passion since it competes with the authority of the father, the foundation of filial piety.

Although not contemporary, ancient Greek civilization undoubtedly provided a cultural foundation for Western civilization. Due to this importance, let us take a brief look at the Greek attitude towards couple love as portrayed in their mythology and literature.

In general, Greek mythology glorifies dysfunctional relationships and contains many extra-marital affairs. The divine couples inhabiting Mount Olympus rarely, if ever, exhibit the passion and bliss contained in the relationship between Rama and Sita. One most frequently thinks of Zeus regularly cheating on his wife Hera. Zeus, the main god, has multiple affairs, including a number with beautiful mortal women.

Homer’s Greek classic, The Odyssey, does provide an excellent example of a loving couple, who must suffer through a great separation before being reunited. Odysseus goes through incredible trials to get back home to his wife, Penelope. While she has been loyal to him during his long absence, Odysseus had an affair. He does eventually leave his lover after years to return to his faithful wife.

While the action of the plot is driven by the hero’s motive to return to his wife, the nature of the love relationship in the Odysseyis very different from the Ramayana. Although this is certainly a great story of love and reunion, Odysseus’ extramarital affair taints it. One can’t imagine Rama’s devotion to Sita compromised in a similar fashion. As ‘soul mates’, they only have eyes for each other.

The notion of ‘soul mates’ seems to be unique to Hinduism. We’ve explored prominent examples from organized religions, spiritual practices, and paternalistic cultures. None of them contain the notion of divine couple love. In fact, the passion of couple love is frequently viewed in an unfavorable light as it is considered to be a distraction from higher religious or social aspirations.

Many religions and cultures of the world tend to ignore or vilify the passion of couple love. In contrast, the widespread Hindu story of the Ramayana suggests that this relationship is a path to profound spiritual experience. In the countries where they are prevalent, these Hindu stories could easily inspire young men and women to imagine their passion for each other as divine and godly. This is certainly a feature of the Ramayana that would contribute to its long-term influence and staying power.

Pursuit of desires important to fulfillment of destiny

In the Ramayana, the passion between Rama and Sita is both a central and positive driving force in the tale. Rama’s passion for Sita inspires him to perform heroic deeds for her sake. To accomplish his task, he drives out all the demons that have enslaved both she and the gods.

The notion that passion is a positive religious force runs counter to the notion that desires are the root of evil. Detachment from our desires is one of the central tenets of both Buddhism and Indian Yoga. Detachment is important because the pursuit of desires presumably ties us to the transitory world of illusion and destroys peace of mind.

In contrast, Rama’s desire to save Sita drives him to accomplish his divine mission. If Rama had taken a Buddhist stance, he could have just as well gone into a monastery and meditated upon the unreality of existence. If a yogi, he could have meditated upon how it is all an illusion, Maya, just part of the mental duality. Instead Rama’s passion for Sita drives him to conquer evil, incarnated as Ravana.

Many modern religious manifestations tend to look down upon couple love as something extraneous and perhaps even detrimental to the religious experience. However, the Hindu story of Rama and Sita inspires coupling and the desires that follow. It presents the image that at certain times pursuing one’s desires is necessary to fulfill the divine plan. The Ramayana is not a tragedy where Rama loses his life and kingdom as a consequence of his passion for Sita. Instead he is able to fulfill his destiny because he never gives up searching for her.

Rama’s attraction for Sita is divinely inspired. Because she is his soul mate, it is meant to be. This is very different from other traditions. Sita does not employ her charms to lure Rama to his doom on the rocks, like the Sirens of Scandinavian myths. Sita is not like Eve, who tempts Adam to eat of the illicit tree, which dooms humankind to toil in the deserts outside the Garden of Paradise. Nor is Sita like the demon ladies in China’s Journey to the West, who were trying to thwart the journey by taking Tripitaka’s vital sperm. Nor is Sita the Virgin Mary who is chaste and pure and only exists to be a mother of the male god.

As is evident, desire in the Ramayana is an essential component driving Rama’s Dharma. Rama’s desire for Sita is not a bodily corruption, which gets in the way. Indeed the passion that Rama and Sita have for each other is frequently portrayed on a high spiritual plane. On this level, their affection for each other reflects the passion for union with divinity. (We will explore this theme in more depth in the next chapter.)

Not only is couple love associated with a Dharma pathway to spirituality, it also represents the power of desire. Perhaps the yearning to couple with one’s lover is the fundamental example of such a desire. Yet the power of desire extends beyond the love relationship to a whole gamut of longings attached to the experiences of this world. Devotion — the spiritual desire to serve divinity, is certainly one of the most important and powerful of these desires.

Devotion is the ultimate desire that drives the Dharma path in the Ramayana. Devotion initially leads to problems, not to peace of mind. On a straightforward level, the desire to serve Rama motivates a vast army of bears and monkeys to leave the safe confines of their forest kingdoms. They endure the privations and dangers of warfare, when they could have easily continued their everyday existence, perhaps even cultivating internal peace of mind. Instead their devotion to Rama draws them to fulfill their Dharma in the turbulence and conflict of the external world.

Besides affirming couple love, the Ramayana also affirms the positive function of desire in the fulfillment of our Dharma/Destiny. Instead of representing a philosophy that counsels one to mitigate and/or detach from all desires, this famous Hindu novel portrays the importance of catching the wave of desire. Pursuing the divine desire leads us to the One. We suggest that this plot element certainly contributed to its universal appeal.

Evil desires of the demons lead to their doom

While the divine desire of Rama and Sita for each other is glorified and made to be their strength, the physical desires of the demon king Ravana certainly lead to his eventual doom. Indeed for Ravana, the pursuit of desire is his fatal flaw. This is a classic Yogic, Buddhist, Taoist and Christian theme. The pursuit of desires at the expense of a divine relationship inevitably leads to disaster.

Sita is gorgeous and is regularly described as such. Her beauty and Rama’s good looks are what drive the story. A female demon becomes obsessed with Rama and a male demon becomes obsessed with Sita, even though both demons know that the object of their obsession is married. While Rama and Sita are made for each other, those with out-of-balance passions are attempting to split them up and take them for themselves. However, this is all part of the plot of the gods, to eradicate the demons from existence. Trick them to come out and then destroy them.

In many ways the story of Ramayana is about the battle between the good desires of Rama and Sita and the bad desires of the demons. This is not a Buddhist or Yogic theme: where desires are bad because they are rooted in the illusion of the transient world of the Mind. Not only is the human world portrayed as real, it is also portrayed as intimately connected with the divine world. Rama’s eventual triumph frees both the humans and gods from the control of demons.

In contrast to many cultural and religious philosophies, the Ramayana tale presents a balanced view of desire. Following the divine desire leads us to our Dharma path, while following corrupted desires leads to destruction. This balanced approach must certainly contribute to its longevity and influence. Instead of addressing an audience comprised of the spiritual elite — yogis, ascetics, monks, the Ramayana focuses upon the concerns of a far more egalitarian audience. The average citizen can easily apply the insights of this famous Hindu text to his or her own life.

Romantic Love in the Secular Context

In our survey of cultural attitudes towards romantic love, we have yet to discuss the secular element of Western society. The transformative power of romantic love does exist in the secular context. Its roots in the West are embedded within the troubadour tradition of Western Europe. These poet minstrels are among the first to reject a love relationship based upon ecclesiastical or paternalistic authority. As such, this new notion of romantic love is deeply connected to the emerging concept of the worth of the individual human being. The minstrels’ songs often glorified the overwhelming mutual attraction that occurs between two individuals, while subtly critiquing the traditional notion of an arranged marriage.

Shakespeare’s classic play, Romeo and Juliet, certainly provides an example of the type of couple love that is unsanctioned by church or family. However, the plotline ends tragically by showing the unbridled excesses of following one’s passions in a world that is not prepared to accept such notions. This couple is so in love that they ultimately view suicide, as the only option to their frustrated hopes. Although the social message of the story may be that two opposing families ultimately learned to get along, the tragic message is that following one’s passions against the cultural tide can be deadly.

Despite the potential for tragedy, our secular world has often embraced the notion of the transformative power of romantic love. This expression has taken myriad forms: fairy tales, romance novels, and romantic comedies to name a few. The secular inflection of these modern renditions, however, lacks the spiritual context of the Ramayana.

The expression of couple love had to emerge in the Western secular world because the ecclesiastical world of religious dogma would not make room for it. However in the East, the Ramayana offers religious validation for this powerful notion of couple love. Indeed this could be another reason the Ramayana was so well received by so many diverse cultures: Its portrayal of the transformative power of couple love as a religious expression is a refreshing difference from the repressive nature of most religious perspectives or texts.

Rama’s Insistence on Sita’s purity, a patriarchal flaw

While the story reflects the importance of couple love as a mechanism for universal good, it has at least one major flaw — Rama’s patriarchal attitude, his insistence on Sita’s purity.

Through great effort over a long period of time, Rama frees Sita from the demons. Although desperately in love with her, as witnessed by his superhuman efforts to win her back, he refuses to see her at first. He hesitates because he is not sure that she hasn’t slept with the demon king, Ravana. To prove that she has not slept with the demon-king, Sita throws herself into a sacrificial fire. However untouched by the fire, she survives the trial proving that she is innocent of any charges against her. Sita and Rama become queen and king of the land, presumably living happily ever after.

Rama’s obsession with Sita’s purity is typical of patriarchal culture. The purity of the woman is overemphasized. She must be pure because it is important that she does not bear a ‘demon’ child. In male-dominated cultures, the purity of the bloodline can only be guaranteed by the purity of the wife. Any possibility that she is bearing the son of another man is the ultimate disaster.

These patriarchal concerns are particularly critical when it comes to the purity of the royal family bloodline. The importance of untainted genetics is rooted in the idea that royal blood is superior to common blood. Traditional kingdoms were obsessed with the rule of primogeniture, where the oldest legitimate son ascends to the throne, or inherits the family estate.

The modern vantage point is that bloodline is not correlated with the ability to rule. It is rare for anyone in a Western democracy to think that the President’s first son should inherit the job.

The point of this whole discussion is that Sita’s purity should not be an issue. If Rama’s love were really that great, he wouldn’t care as much about what happened while they were separated, would care far more about the happy fact of their reunion. Rama’s obsession with Sita’s sexual purity seems to be a misplaced patriarchal throwback.

If the story were to be retold, the story need not end with Rama testing Sita’s purity. Instead he could say, “Darling, your ordeals are over and that is what’s most important. We are back together and I don’t care what went on while we were separated because I trust you. I am just grateful that we are joined together again and in good health and vitality. Let our bodies merge together as an external manifestation of our internal love.”

Modern democracies don’t employ primogeniture to determine leaders. Similarly, marriage counselors don’t stress the notion of sexual purity, as a prerequisite for a loving relationship. The idea of testing the virginity of the bride is only done in the most patriarchal of societies. The modern American woman feels that she should be as sexually liberated as the man. Indeed most relationships can survive a single affair and last into old age. If a single sexual infidelity is the only problem a relationship has, the counseling is generally to forgive, if not forget.

While affirming couple love as a whole, the conclusion of the Ramayana gets stuck in an obsession with sexual purity at the expense of a loving compassionate relationship. In other words, this theme is not universal at all, and is instead particular to the period in which it was composed.

In summary, part of the enduring and universal appeal of the Ramayana has to do with its portrayal of the passion of couple love as a positive spiritual force. Rama’s love of Sita drives him to conquer evil in the form of Ravana. As a powerful warrior king, he is not defending his country from attack, nor is he on a crusade against evil, nor is he simply following a code of chivalry. He is instead responding to his healthy passion for his soul mate, Sita. As a lover, Rama is inspired to action to protect his soul mate. As a warrior, he is able to destroy his enemy and rescue his wife, thereby restoring harmony to the universe. The unique story of the Ramayana is inspirational to couples wherever Hindu myths are told.

‘*’ An academic colleague wrote: “The idea of soulmates comes from Emanuel Swedenborg’s work — specifically his book Conjugial Love, which was adopted and adapted by Americans like Andrew Jackson Davis to support divorce law ‘I’ve decided that so-and-so isn’t my soulmate, but that other so-and-so is.’”